DELLA VERA ARTE DI

adoprare le arme.

Cap. I.

The true Art of Defense

exactly teaching the manner how to handle weapons safely, as well offensive as defensive, with a Treatise of deceit or Falsing, And with a mean or way how a man may practice of himself to get Strength, Judgment, and Activity.

NON Ú dubio alcuno l'essercitio honoratissimo de l'arme farsi per due cose perfettissimo, cioe per il giuditio,& per la forza , percioche da l'uno s'acquista la cognitione, del modo & del tempo di operare in qual si uoglia accorrenza,& da l'altro si sa habili a poter il tutto esequire in tÚpo debito & con auantagio, per theil cono scer il modo & iÚpa di ferire e riparar per se solo gioua solamente al saperne ragionare, il fine di quest'arte non e il dire ma il fa re.onde a uoler in essa riuscire quanto si conuiene egli e dibisogno oltra l'hauer guiditio, hauer anco modo di poter prestissimo esequire quel tanto che il giuditio comprehende & uede, & questo non si puo fare se non con la forza & destrezza del corpo, la quale se perauentura Ú debole o tarda ouero che non pu˛ sostentare i pesi delle botte, ouero per non andar a ferir quando il tempo richiede resta auilluppato. i quali errori come si uede , non procedono da l'arte ma da l'instrumÚto mal accomodato ad exequirla; perˇ s'af faticherÓ ogn'uno che uorrÓ in quest' adoperarsi di acquistar questa forza,tenendo per certo che il giuditio fenza questa forza & destrezza sia o di poca o di niuna utilita,ma forse di danno, percioche gli huomini acietati dal giuditio, per sapere come le co se si debbano fare, si pongono a imprese nelle quali poscia non riescono in fatti; ma percioche il dir che la forza a quest'arte sia necessaria & non dar il modo d'acquistarla , essendo ella uno de dua capi principali farebbe un fondar l'arte infogni & inchimere, percio ho deliberato in principio di quest'epra dare il modo di acquistar il giuditio, & in fine di essa far un trattato come l'huom˛ si possa da se stesso esercitare per acquistar, forza & prestezza, modo per quanto a quest'arte appertiene, di modo che potra ciascuno con le ragioni che si daranno diuenir senz'altro maestro & presto& forte.

There is no doubt but that the Honorable exercise of the Weapon is made right perfect by means of two things, to wit: Judgment and Force: Because by the one, we know the manner and time to handle the weapon (how, or whatsoever occasion serves:) And by the other we have the power to execute therewith, in due time with advantage. And because, the knowledge of the manner and Time to strike and defend, does of itself teach us the skill how to reason and dispute thereof only, and the end and scope of this Art consists not in reasoning, but in doing: Therefore to him that is desirous to prove so cunning in this Art, as is needful, It is requisite not only that he be able to judge, but also that he be strong and active to put in execution all that which his judgment comprehends and sees. And this may not be done without strength and activity of body: The which if happily it be feeble, slow, or not of power to sustain the weight of blows, Or if it take not advantage to strike when time requires, it utterly remains overtaken with disgrace and danger: the which faults (as appears) proceed not from the Art, but from the Instrument badly handled in the action. Therefore let every man that is desirous to practice this Art, endeavor himself to get strength and agility of body, assuring himself, that judgment without this activity and force, avails little or nothing: Yea happily gives occasion of hurt and spoil. For men being blinded in their own judgments, and presuming thereon, because they know how, and what they ought to do, give many times the onset and enterprise, but yet, never perform it in act. But least I seem to ground this Art upon dreams and monstrous imaginations (having before laid down, that strength of body is very necessary to attain to the perfection of this Art, it being one of the two principal beginnings first laid down, and not as yet declared the way how to come by and procure the same) I have determined in the entrance of this work, to prescribe the manner how to obtain judgment, and in the end thereof by way of Treatise to show the means ( as far as appertains to this Art) by the which a man by his own endeavor and travail, may get strength and activity of body, to such purpose and effect, that by the instructions and reasons, which shall be given him, he may easily without other master or teacher, become both strong, active and skillful.

DEL MODO DI AQUISTAR

il gluditio.

The means how to obtain Judgment

PER molto che io quali in tutte le parti d'Italia habbia ueduto professori eccelentisimi di quest'arte,& insegnar nelle lor schuo le & exercitar secretamente per condur in stecato: non so di hauer ne ueduto alcuno,ýlgual habbia posseduta questa parte del giuditio come si conuiene puo e▀er che l habbino & che la tenghino p¨re tra molei colpi sregolati, se ne ueggono di bellissimi et giuditiosissimimi, ma sia com˙q sý uoglia,io hauendo intentione di .giouar in quest'arte quanto posso , uoglio in questa parte dir tutto quello che mi pare a proposito. Deuesi dunque sapere che l'huomo in tanto diuiene timido & ardito in quanto conosce di poter uietar non uietar il pericolo, ma per hauer questa cognitione, eglie di bisogno hauer continuamente nella memoria fili tutti gli infrascri ti auertimenti, dai quali nafte tutta la cognitione di quest'arte, ne e possibile senza questi far cosa con ragione ne che sia bona et so pu re auiene che alcuno senza hauer saputo questi, habbia fatto cosa con giuditio & utile, questo non uiene da altro,che dalla natura anima, la quale per f conosce tutti questi auertimenti, i quali son questi, che la linea retta e la piu breue d ognaltra & pero qua do si uorra ferir per la piu corta sara di bisogno ferir per la li, nea retta. il secondo d , chi e piu uicino giunge piu presto, dal qual auertimento nasce questa, utilitÓ che uedendosi la spada da de l'inimico lontana o alta per ferire all'hura si ferisce prima che esser ferito , il terzo Ú che un cerchio che giri ha maggior forza nella circonferenza, che uerso il centro, Il quarto che piu facilmente si resiste alla poca che alla molta forza, Il quinto che ogni moto Ŕ fatto in tempo. Che da questi auertimenti ne nafta il giuditio e cola chiari▀ima, percio che altro,non si ricercha in quest'arte che ferir con auantaggio & difendersi sicuramente,il che sý fa ferendo per linea retta di punta, o di taglio dotte la spada ha piu tori ferendo prima l'inimico che esser ferito, il che si fa qua╗ do si conosce di esser piu uicino all'inimico , ne quali casi si spinge, per che pochi o niuno Ŕ che sentendo si ferir non dia i╗ dietro regi di fare ogn'altro moto c'hauesse incominciato, & sapendo poi che ogni moto si fa in tempo , si procura per ferir & riparar di far manco moti che sia possibile per consumar poco tempo , & tacendone molti l'inimico , si puo star auertito di ferirlo, fotto uno o piu tempi indebitamente consumati,

Although I have very much in a manner in all quarters of Italy, seen most excellent professors of this Art, to teach in their Schools, and practice privately in the Lists to train up their Scholars. Yet I do not remember that I ever saw any man so thoroughly endowed with this first part, to wit, Judgment, that behalf required. And it may be that they keep it secret of purpose: for amongst diverse disorderly blows, you might have seen some of them most gallantly bestowed, not without evident conjecture of deep judgment. But howsoever it be seeing I purpose to further this Art, in what I may, I will speak of this first part as aptly to the purpose, as I can. It is therefore to be considered that man by so much the more waxes fearful or bold, by how much the more he knows how to avoid or not to eschew danger. But to attain to this knowledge, it is most necessary that he always keep steadfastly in memory all these advertisements underwritten, from which springs all the knowledge of this Art. Neither is it possible without them to perform any perfect action for the which a man may give a reason. But if it so fall out that any man (not having the knowledge of these advertisements) perform any sure act, which may be said to be handled with judgment, that proceeds of no other thing, than of very nature, and of the mind, which of itself naturally conceives all these advertisements.

- First, that the right or straight Line is of all other the shortest: wherefore if a man would strike in the shortest line, it is requisite that he strike in the straight line.

- Secondly, he that is nearest, hits soonest. Out of which advertisement a man may reap this profit, that seeing the enemies sword far off, aloft and ready to strike, he may first strike the enemy, before he himself be struck.

- Thirdly, a Circle that goes compassing bears more force in the extremity of the circumference, than in the center thereof.

- Fourthly, a man may more easily withstand a small than a great force.

- Fifthly, every motion is accomplished in time.

That by these Rules a man may get judgment, is most clear, seeing there is no other thing required in this Art, than to strike with advantage, and defend with safety. This is done, when one strikes in the right line, by giving a thrust, or by delivering an edgeblow with that place of the sword, where it carries the most force, first striking the enemy before he be struck: The which is performed, when he perceives himself to be more near his enemy, in which case, he must nimbly deliver it. For there are a few nay there is no man at all, who (perceiving himself ready to be struck) gives not back, and forsakes to perform every other motion which he has begun. And forasmuch, as he knows that every motion is made in time, he endeavors himself so to strike and defend, that he may use as few motions as is possible, and therein to spend as little time. And as his enemy moves much in diverse times he may be advertised hereby, to strike him in one or more of those times, so out of all due time spent.

DELLA DIVISIONE

de l'arte.

The division of the Art

PRIMA che si uenga a piu particolare dichiaratione di questa arte , fÓ dibisogno diuiderla ; onde Ú da' sapere che si come quasi in tutte l'altre arti, in questa ancora, gli huomini, lasciando la uera scienza sperando forse piu con la bugia , che con il nero uittoriosi , hanno trouato un nuouo modo di schermir pieno di finte & di inganni ilquale essendo di qualche utilitÓ contra quelli che o sono timidi , o sono ignoranti de i princip , pero fino sforzato a diuidere quest'arte in due. , chiamando l'una , uera , & laltra, inganneuole ; auertendo per˛ ciascuno , l'inganno contra la uera arte non esser di profitto alcuno anzi,di grandissimo danno & mortale a chi l'usa; lasciando dunque da parte per hora.l'inganno delquale si tratterÓ poi a suo loco & restringendomi alla ueritÓ laquale e il uero & principal desiderio del anima nostra, presuponendo che la giustitia uicinissima alla ue- ritÓin ogni occasione sia sempre superiore , dico a chiunque uol in tal mestiero essercitarsi ; gli e dibisogno hauer fornivo giuditio, ani moso core, & gran prestezza nelle quali tre cose si mantiene Ú ui ue tutto questo esercitio.

Before I come to a more particular declaration of this Art, it is requisite I use some general division. Wherefore it is to be understood, that as in all other arts, so likewise in this (men forsaking the true science thereof, in hope peradventure to overcome rather by deceit than true manhood) have found a new manner of skirmishing full of falses and slips. The which because it somewhat and sometimes prevails against those who are either fearful or ignorant of their grounds and principals, I am constrained to divide this Art into two Arts or Sciences, calling the one the True, the other, the False art: But withal giving every man to understand, that falsehood has no advantage against true Art, but rather is most hurtful and deadly to him that uses Therefore casting away deceit for this present, which shall hereafter be handled in his proper place and restraining myself to the truth, which is the true and principal desire of my heart, presupposing that Justice (which in every occasion approaches nearest unto truth) obtains always the superiority, I say whosoever minds to exercise himself in this true and honorable Art or Science, it is requisite that he be endued with deep Judgment, a valiant heart and great activity, In which three qualities this exercise does as it were delight, live and flourish.

DELLA SPADA.

Of the Sword

ANCORA che le arme si da offesa come da diffesa siano quasi infinite,percioche tutto quello che puo l'huomo adoprar per offender altri o per difender se o lanciando, o tenendo in mano mi pare che si possa adimandar arme,nulla dimeno perche quelle com'ho detto sono inumerabili , di modo che a uoler particolarmente di tutte trattar, oltra che ella sarebbe una fatica grandissima , la sarrebbe ancho senza dubio inutile , percioche i principi 9 auertimenti che si danno in questa : seruono per tutte le arme usate & che, forse s'useranno, lasciando dunque tutte quel le che per bora non fanno Ó nostro proposito dico non esser tra tutte l'armi che hogidi s'usano,la piu honorata,la piu frequentata,ne la pi¨ semplice della spada , onde a, questa uenendo prima come quella,nella qual solo si fonda la uera scienza di quest'arte, fendo che per hauer longhezza mediocre tagli & punta , molto con ciascun'altra s'assimigli, pero e da sapere che non hauendo ella piu che duo tagli & una punta,non si puo con altri che con questi ferire, ne altri che questi s'ha da schifare, & tutti i colpi di taglio , o sia dritto o fa riuerso , formano o cerchio ˇ parte di cerchio del quale la mano e il centro, & il meso diametro e la lunghezza d'urna spada, onde glie di bisogno uolendo ferir di taglio per esser gran giro , ouero anco di punta glie dibisogno dico esser presto di mano & conoscere il tempo de l'auantagio , il qual consiste nel conoscer, quando la propria spada e piu uicina a ferir che quella de l'inimico perche se l'inimico per ferir giraffe la sua spada un bracÝo ritrouandosegli in quel calo uicino mezzo braccio , non si deue curar di riparare, ma ferire, perche giongendo prima, si uiete ra il cader a l'inimica spada, essendo pura constretto a riparar alcun colpo di taglio, si deue per maggior sicurezza & facilita, an dare ad'incontrar da mezza spada indietro,nel qual loco la spada nemica ha manco forza & si ritroua piu uicina per ferir l'inimico. .Quanto a i colpi di punta molto periculosi, si deue procurar di filar in modo con la uita, co'i piedi, con le braccia, che non si a bisogno uolendo ferir perder un tempo,iichesifa quando si ila o col bracio tanto inanti,o coi piedi tanto indietro o con la.uita tanto di sadata,che prima che si spinga sia di bisogno o ritirar il braccio o aitarsi dei piedi o far moto con la uita,di che accortosi l'inimicosi puo prima ferir che er ferito, ma stando nel debito modo che si mostrera conoscendo di esser manco distaza da la sua punta di spada all'inimico, che da quella dell'inimico a se si deue in quel caso con prestezza gagliardamente spingere che si giungera prima.

Albeit Weapons as well offensive as defensive be infinite, because all that whatsoever a man may handle to offend another or defend himself, either by flinging or keeping fast in his hand may in my opinion be termed Weapon. Yet notwithstanding, because, as I have before said, they be innumerable so that if I should particularly handle every one, besides the great toil and travail I should sustain, it would also doubtless be unprofitable, because the principals and grounds which are laid down in this Art, serve only for such weapons as are commonly practiced, or for such as happily men will use: and so leaving all those which at this present make not for my purpose, I affirm, that amongst all the weapons used in these days, there is none more honorable, more usual or more safe than the sword. Coming therefore first to this weapon, as unto that on which is grounded the true knowledge of this Art, being of reasonable length, and having edges and point, wherein it seems to resemble every other weapon, It is to be considered, that forasmuch as it has no more than two edges and one point, a man may not strike with any other than with these, neither defend himself with any other than with these. Further all edge blows, be they right or reversed, frame either a circle or part of a circle: of the which the hand is the Center, and the length of the sword, the Diameter. Whereupon he that would give either an edge blow in a great compass, either thrust with the point of the sword, must not only be nimble of hand, but also must observe the time of advantage, which is, to know when his own sword is more near and ready to strike than his enemy's. For when the enemy fetches a compass with his sword, in delivering his stroke, at the length of the arm: if he then perceive himself to be nearer by half an arm, he ought not to care to defend himself, but with all celerity to strike. For as he hits home first, so he prevents the fall of his enemies sword. But if he be forced to defend himself from any edge blow, he must for his greater safety and ease of doing it, go and encounter it on the half sword that is hindmost: in which place as the enemies sword carries less force, so he is more near at hand to offend him. Concerning thrusting, or the most perilous blows of the point, he must provide so to stand with his body, feet and arms, that he be not forced, when he would strike, to lose time: The which he shall do, if he stand either with his arm so forward, either with his feet so backward, either with his body so disorderly, that before he thrust he must needs draw back his arm, help himself with his feet, or use some dangerous motion of the body, the which when the enemy perceives, he may first strike before he be struck. But when a man stands in due order (which shall hereafter be declared) and perceives that there is less distance from the point of his sword unto his enemy, than there is from his enemies sword unto him, In that case he must nimbly force on a strong thrust to the end he may hit home first.

DELLA DIVISIONE DELLA SPADA.

The division of the sword

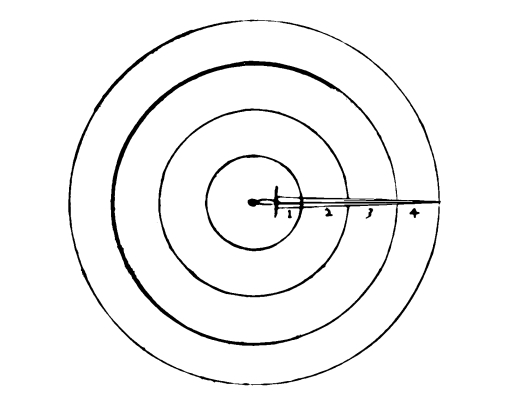

NON e▀endo gli effetti della lunghezza della spada in ogni par te eguali, Ú ragioneuol cosa oltra il farne conoscer la causa, ritrouar di ciascuno la sua proprietÓ & nome accio po▀amente ciascuno sapere quali sian le parti con che egli ha da ferire & con quali debba schifare. Altroue ho detto la spada nel ferire formar o cerchio o parte di cerchio' del quale la mano e il centro; & Ú manifesto che una rota che gira, ha maggior forza & uelocitÓ nella circonferenza che uerso il centro, alla qual ruo, ta sendo simili▀ima la spada nel ferire; ci pare di diuiderla in quattro parti eguali; delle quali quella piu uicina alla mano come piu uicina alla causa dimandaremo prima, la sequente seconda ,poi terza,& quarta la parte che contiene la punta , delle quali la terza & quarta useremo per ferir, per che essendo piu uic, ne alla circonferenza sono piu ueloci & la quarta non nella punta ma quattro ditta piu in dentro sara piu ueloce & forte di ciascun' altra; percioche oltra l'esser nella circonferenza per la quale han maggiore uelocitÓ hanno ancora quattro ditta di ferro di contrapeso che -li da nel moto maggior furia. Le altre due particioe' prima & se conda useremo per riparare, per cioche quelle per ferir hauendo poco giro han poca forza & per resister a un'empito per esser uicine alla mano che Ú causa sono piu forti

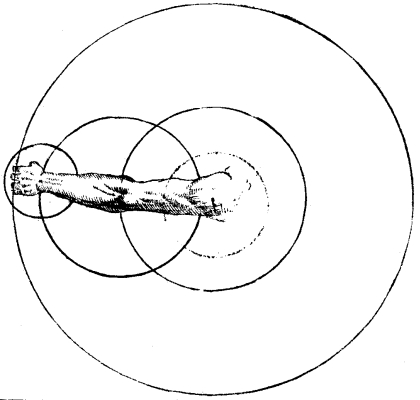

Non Ú parimente il braccio in ogni parte della istessa forza & uelocitÓ, anzi per ogni piegatura differente, cioŔ nella giuntura della mano ,nel gomito & nella spalla, & il colpo di nodo di mano cioŔ della giuntura della mano che e piu ueloce e manco forte, & gli altri doi si come son piu forti son piu tardi, per cio che fanno maggior giro, pero per mio consiglio nˇ si dee uolendo ferýre di taglio far il giro della spalla, perche portandosi la spada troppo lontana, si da tempo al'accorto inimico di entrar prima, ma usar solamente il giro del gombitto & il nodo di mano i quali oltra che sono presti▀imi sono ancho forti quando si sanno trar.

For as much as the Effects which proceed from the length of the sword, are not in every part thereof equal or of like force: It stands with reason besides the declaration of the cause, that I find out also the property and name of each part, to the end every man may understand, which are the parts of the length wherewith he ought to strike, and which the parts, wherewith he must defend. I have said elsewhere, that the sword in striking frames either a Circle, either a part of a Circle, of which the hand is the center. And it is manifest that a wheel, which moves circularly, is more forcible and swift in the circumference than towards the Center: The which wheel each sword resembles in striking. Whereupon it seems convenient, that I divide the sword into four equal parts: of the which that which is most nearest the hand, as mostnigh to the cause, I will call the first part: the next, I will term the second, then the third, and so the fourth: which fourth part contains the point of the sword. of which four parts, the third and fourth are to be used to strike withal. For seeing they are nearest to the circumference, they are most swift. And the fourth part (I mean not the tip of the point, but four fingers more within it) is the swiftest and strongest of all the rest: for besides that it is in the circumference, which causes it to be most swift, it has also four fingers of counterpiece thereby making the motion more forcible. The other two parts, to wit, the first and second are to be used to warde withal, because in striking they draw little compass, and therefore carry with them small force And for that their place is near the hand, they are for this cause strong to resist any violence. The Arm likewise is not in every part of equal force and swiftness, but differs in every bowing thereof, that is to say in the wrist, in the elbow and in the shoulder: for the blows of the wrist as they are more swift, so they are less strong: And the other two, as they are more strong, so they are more slow, because they perform a great compass. Therefore by my counsel, he that would deliver an edgeblow shall fetch no compass with his shoulder, because whilst he bears his sword far off, he gives time to the wary enemy to enter first: but he shall only use the compass of the elbow and the wrist: which as they be most swift, so are they strong in ought, if they be orderly handled.

CHE OGNI COLPO DI PUNTA FERISCA

circularmente & come ferendo di punta si ferisca rettamente.

That every blow of the point of the sword strikes circularly and how he that strikes with the point, strikes straight.

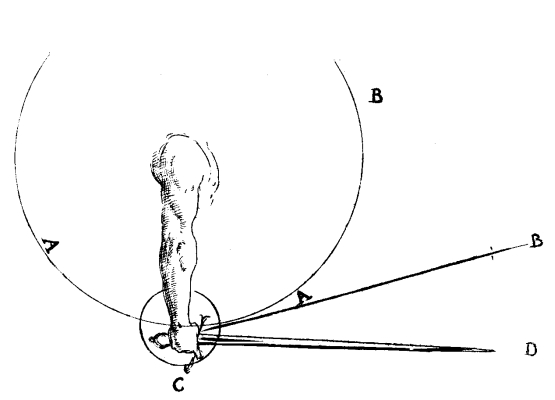

HAVENDO detto di sopra & posto per una de principy di questa arte Che la linea retta e la piu breue di tutte l'altre il che e uerissimo, ne ha punto bisogno di dimo▀ratione & che poi hauendo come per uero suggetto che il ferir di punta sia ferir rettamente non essendo ciao semplicemente vero parmi raggioncuole prima che si uada piu inanti dimostrare come i colpi di punta feriscano circularmente & come rettamente il che mi sforzera di fare con quella maggior chiarezza & breuitÓ che possibil sia, ne mi estender˛ in parlare de i colpi di taglio, & come tutticircularmente feriscano sendosene di cio abbondante & chiaramen te trattato nella diuisione del braccio & della spada. Venendo dunque a quello che e nostra intenti ne di trattare in questo luogo principalmente diro prima come il braccio in ferir di punta ferisca circularmente. E chiara cosa che tutti i corpi di figura, retta o lunga che uogliam dire quando hanno un capo fermo immobile & che si muouano con l'altro capo sempre & necessariamente in mouendosi formeranno una o parte di figura circulare. sendo dunque una tale figura il braccio ilquale ha la sua parte fissa & imobile nella.spalla & si muoue solamente con la parte di sotto non e dubio alcuno che esso ancora non formi in mouendosi o cerchio o parte di esso , ilche puo ciascuno per suo proprio essempio in mouendo il proprio braccio conoscere. se questo dunq; Ú come e' necessariamÚte uero sarÓ anco uero che tutte quelle cose che saranno a esso braccio attaccate mouendosi al moto di esso braccio si debbano circularmente mouere & questo sia quanto al primo proposito. Venir˛, dunque al secondo & mostrero le ragioni per lequali ferendo di punta si ferisca rettamente dico che qual uolta la spada sarÓ mossa dal solo moto del braccio che sempre & necessariamente formerÓ cerchio per le ragioni gia dette, ma se auiene come quasi sempre auiene che il braccio in mouendo ormi un cerchio a l'insu, & la mano mouendosi nel nodo formi una parte di cerchio al'ingiu, al'hora accaderÓ che questa spada mossa da questi doi contrarii moti in andando innanzi possa rettamente ferire & perche ciao pia c chiaramente si conosca ne f ormero la presente figura per intelligeniia della quale e da sapere che si come il braccio in mouendo porta reco la spada & cagione ch'ella dal medesimo moto spinta formi cerchio, al'infu cosi la mano mouendosi nel suo nodo puo inalzare & abbassare la punta a l'ingiu, onde abbassando essa mano la punta della spada tanto quanto il braccio inalza il manico,auiene che la spada ua a ferir di punta nel punto retto che si mira . sarÓ dunque il cerchio A B quello che e fatto dal moto del braccio, il quale braccio se portando seco nel suo moto la spada uolesse ferir rettamente nel punto. D. andarebbe nece▀itato dal suo moto a ferir nel punto. B & di qui nasce la difficultÓ del ferir giusto de punta. Se dunque uorrÓ rettamente esso braccio ferir nel punto.D.sarÓ dý bisogno quanto esso inalza il manico, che il nodo di mano mouÚ dosi circularmente a l'ingiu & formando il cerchio A C Questo tirando seco la punta della spada a l'ingiu la fa di nece▀ita andar a ferir nel punto. D. ilche non auenirebbe se con un solo moto del braccio ilquale si muoue sopra il centro E. si uolesse spinger la spada sendo adunque per mio .auifo manifesto che il ferir di punta non e semplicemente et per un solo moto rettamente fatto ma in uertu di doi moti circolari cioŔ del braccio & del la mano lo nominero in tutta l'opra ferir per linea retta ilche per le ragioni dette non e punto inconveniente.

Having before said and laid down for one the principals of this art, that the straight Line is the shortest of all others (which is most true.)It seems needful having suggested for a truth, that the blow of the point is the straight stroke, this not being simply true, I think it expedient before I wade any further, to show in what manner the blows of the point are struck circularly, and how straightly. And this I will strain myself to perform as plainly and briefly as possibly I may. Neither will I stretch so far as to reason of the blows of the edge, or how all blows are struck circularly, because it is sufficiently and clearly handled in the division of the Arm and the sword. Coming then to that which is my principal intent to handle in this place, I will show first how the arm when it strikes with the point, strikes circularly. It is most evident, that all bodies of straight or long shape, I mean when they have a firm and immovable head or beginning, and that they move with an other like head, always of necessity in their motion, frame either a wheel of part of a circular figure. Seeing then the Arm is of like figure and shape, and is immovably fixed in the shoulder, and further moves only in that part which is beneath it, there is no doubt, but that in his motion it figures also a circle, or some part thereof. And this every man may perceive if in moving his arm, he make trial in himself. Finding this true, as without controversy it is, it shall also be as true, that all those things which are fastened in the arm, and do move as the Arm does, must needs move circularly. This much concerning my first purpose in this Treatise. Now I will come to my second, and will declare the reasons and ways by which a man striking with the point strikes straightly. And I say, that whensoever the sword is moved by the only motion of the Arm, it must always of necessity frame a circle by the reasons before alleged. But if it happen, as in a manner it does always, that the arm in his motion makes a circle upwards, and the hand moving in the wrist frame a part of a circle downwards the it will come to pass, that the sword being moved by two contrary motions in going forwards strikes straightly. But to the intent that this may be more plainly perceived, I have framed this present figure for the better understanding whereof it is to be known, that as the arm in his motion carries the sword with it, and is the occasion that being forced by the said motion, the sword frames a circle upwards, So the hand moving itself in the wrist, may either lift up the point of the sword upwards or abase it downwards. So that if the hand do so much let fall the point, as the arm does lift up the handle, it comes to pass that the swords point thrusts directly at an other prick or point than that it respects. Wherefore let A.B. be the circle which is framed by the motion of the arm: which arm, if ( as it carries with it the sword in his motion ) it would strike at the point D. it should be constrained through his motion to strike at point B. And from hence proceeds the difficulty of thrusting or striking with the point. If it therefore the arm would strike directly at the point D. it is necessary that as much as it lifts the handle upwards, the hand and wrist do move itself circularly downward, making this circle AC and carrying with it the point of the sword down-wards, of force it strikes at the point D. And this would not so come to pass, if with the only motion of the arm, a man should thrust forth the sword, considering the arm moves only above the center C. Therefore seeing by this discourse it is manifest that the blow of the point, or a thrust, cannot be delivered by one simple motion directly made, but by two circular motions, the one of the Arm the other of the hand, I will hence forward in all this work term this blow the blow of the straight Line. Which considering the reasons before alleged, shall breed no inconvenience at all.

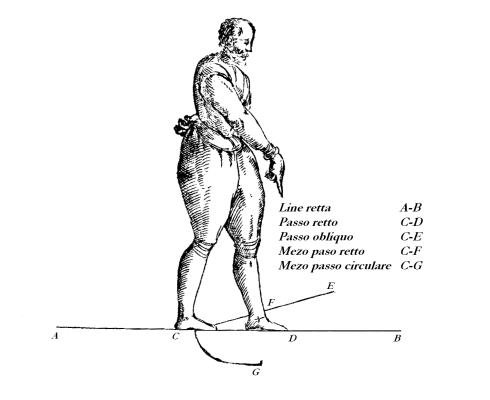

GRANDISSIMA consideratione rechiegono i passi in questo esercitio, percioche da essi quasi piu che da ogn'altra cosa nascono le offese & diffese & la uita parimenti si deue con ogni industria lenir ferma & falda, uolta uerso l'inimico piu presto con la spalla destra che con il petto, & cio per far manco bersaglio di se che sia posibile, & douendola tenir in qualche parte piegata far che pieghi piu presto in dietro che inanti affine che sia lontana da l'offesa non potendo maximamente mouersi mai la ui la in parte alcuna per piu di lei in quella medesima parte non si muoua la testa parte di tanta importanza perˇ quando si uuo ,le andare a ferir si spingono inanti i piedi o le braccia secondo che in quel caso torna meglio, percioche quando auiene che si possa coglier gagliardamente l'inimico senza crescer il passo, cio si deue fare & usar solamente le braccia tenendo pur sempre la uita per quanto si puo & richiede ferma & immobile ;onde non si loda la maniera di schermir di quelli che tutta uia si fanno hora piccioli hora grandi hora torcono uerso una parte hora uerso laltra che paiono biscie, percioche tutti questi son moti, non se ne possono far tanti in una uolta, unde se son ba▀i , per ferir in alto bisogna che prima si leuino, & in quel tempo possono esser feriti, & il simile quando son uolti uerso l'una ˛ latra parte, percio si starÓ nel modo detto sforzandosi a piu poter uolendo ferir ˛ riparar di far cio non in duo tempi, & duo moti, ma in mezo , tempo & moto se po▀ibil fusse Quanto al moto de i piedi da quali nascono le grandi offese & difese; hauendosene molti essempi, che si come il saperli ordinatamente & con ragione mouere caus˛, si , ne, i, stecati, come nelle brighe che tutto di si fanno, honorata uittoria, cosi il troppo mouerli & senza ragione su causa di grandi▀imi danni & uergogne per cio non sene potendo dar certa misura per la diuersitÓ de huomini grandi & piccioli, ad alcuno de quali torna como do il fare passo d'un braccio, ad altri di mezzo o piu per cio farÓ ciascuno auertito di formar in tutte le guardie un passo mediocre, di modo che si po▀i , per uoler crescer a ferir allungarlo un piede, & altrotanto ristringerlo per saluarsi, senza pericolo, di cadere; Ma perche i piedi in questo esercitio si muo buono in diuersisi modi sia buono dir il nome di ciascuno atti che tifandoli per tutta l'operai f a inteso deuesi dunque sapere che i piedi si muoiono o rettamente o circularmente, se rettamente o inanzi o in dietro, et possonˇ mouendosi inanzi rettamente o uero muouere un passo intiero ilche si intende quando si porta il piede di dietro innanzi tenendo fermo quello che era dinanti; & questo passo alle uolte si fÓ diritto alle uolte obliquo, diritto si intende per retta linea & questo di raro accade, obliquo intendo quÓdo il piede di dietro si porta pur dinanzi ma di trauerso portÓ do con esso crescendo inanti la uita fuor della linea retta oue si se risce , il medesmo si intende indietro, ma si usa in dietro piu diritto che obliquo, la metÓ di questi indietro o inanti s'adimanderan mezzi pa▀i, cio e quando si porta il pie di dietro appresso quel di nanti fermandolo,& quando si cresce quel dinanzi, similmente raccogliendo quel dinanzi appresso quel di dietro affermandolo & poscia ritirando quel di dietro questi mezzi pa▀i s'usano molto & retti & obliqui. habbiamo dunque pa▀i diritti & pa▀i obliqui inanti & indietro & parimente mezzi passi inanti indietro diritti & obliqui. Decirculari non s'usano altro che mezzi pa▀i & anco questi si fanno quando hauendo formato il passo e di bisogno girar l'un de'piedi quel di dietro o quel dinanti nella parte destra o sinistra, onde si ha che i pa▀i in cerchio si fanno quando il piede di dietro stando pur di dietro si muoue nella parte destra o sinistra , & quel dinanzi stando tutta uia dinanzi si mouoe anch'egli alla destra o sinistra, con tutti questi pa▀i si puo muouere in tutte le parti, & crescer & ritirarsi.

Most great is the care and considerations which the paces or footsteps require in this exercise, because from them in a manner more than from any other thing springs all offense and Defense. And the body likewise ought with all diligence to be kept firm and stable, turned towards the enemy, rather with the right shoulder, than with the breast. And that because a man ought to make himself as small a mark to the enemy as possible. And if he be occasioned to bend his body any way, he must bend it rather backwards than forwards, to the end that it be far off from danger, considering the body can never greatly move itself any other way more than that and that same way the head may not move being a member of so great importance. Therefore when a man strikes, either his feet or his arm are thrust forwards, as at that instant it shall make best for his advantage. For when it happens that he may strongly offend his enemy without the increase of a pace, he must use his arm only to perform the same, bearing his body always as much as he may and is required, firm and immovable. For this reason I commend not their manner of fight, who continually as they fight, make themselves to show sometimes a little, sometimes great, sometimes wresting themselves on this side, sometimes on that side, much like the moving of snails. For as all these are motions, so can they not be accomplished in one time, for if when they bear their bodies low, they would strike aloft, or force they must raise themselves, and in that time they may be struck. So in like manner when their bodies are writhed this way or that way. Therefore let every man stand in that order, which I have first declared, straining himself to the uttermost of his power, when he would either strike or defend, to perform the same not in two times or in two motions, but rather in half a time or motion, if it were possible. As concerning the motion of the feet, from which grow great occasions aswell of offense as Defense, I say and have seen by diverse examples that as by the knowledge of their orderly and discreet motion, aswell in the Lists as in common frays, there has been obtained honorable victory, so their busy and unruly motion have been occasion of shameful hurts and spoils. And because I cannot lay down a certain measure of motion, considering the difference between man and man, some being of great and some of little stature: for to some it is commodious to make his pace the length of an arm, and to other some half the length or more. Therefore I advertise every man in all his wards to frame a reasonable pace, in such sort that if he would step forward to strike, he lengthen or increase one foot, and if he would defend himself, he withdraw as much, without peril of falling. And because the feet in this exercise do move in diverse manners, it shall be good that I show the name of every motion, to the end that using those names through all this work, they may the better be understood. It is to be known that the feet move either straightly, either circularly: If straightly, then either forwards or backwards: but when they move directly forwards, they frame either a half or a whole pace. By whole pace is understood, when the foot is carried from behind forwards, keeping steadfast the forefoot. And this pace is sometimes made straight, sometimes crooked. By straight is meant when it is done in a straight line, but this does seldom happen. By crooked or slope pace is understood, when the hindfoot is brought also forwards, but yet a thwart or crossing: and as it goes forwards, it carries the body with it, out of the straight line, where the blow is given. The like is meant by the pace that is made directly backwards: but this back pace is framed more often straight than crooked. Now the middle of these back and fore paces, I will term the half pace: and that is, when the hindfoot being brought near the forefoot, does even there rest: or when from thence the same foot goes forwards. And likewise when the forefoot is gathered into the hindfoot, and there does rest, and then retires itself from hence backwards. These half paces are much used, both straight and crooked, forwards and backwards, straight and crooked. Circular paces, are not otherwise used than in half paces, and they are made thus: When one has framed his pace, he must fetch a compass with his hind foot or fore foot, on the right or left side: so that circular paces are made either when the hindfoot standing fast behind, does afterwards move itself on the right or left side, or when the forefoot being settled before does move likewise on the right or left side: with all these sort of paces a man may move every way both forwards and backwards.

DELLA CONVENIENTIA DEL

piede & della mano.

OF THE AGREEMENT

of the foot and hand

LA GAMBA diritta deue sempre esser fortezza della man diritta, & similmente la sinistra della sinistra onde qual uolta accaderÓ di spingere una puntÓ, il douer uole che ella si a dalla gamba accompagnata, perche altrimenti dalla furia & dal peso che Ŕ fuor della linea perpendicolar della uita non hauendo sotto alcuno puntello si ua a rischio di cadere, & si deue sapere che tanto naturalmente cresce & minuisce il passo quanto la mano, per˛ si uede che quando si ha il pie desiro indietro la mano ancora ui si ritruoua, & sforzandosi di star in altro modo si fa uiolenza alla natura , & non i puo durare; onde quando si forma una guardia tenendo la mano allargata il piede anchora si conduce per fortezza uerso quella parte, quando si ha la mano bassa & similmente il pie deliro inanti, uolendo leuar la mano in alto si a anco dibisogno ritirar il piede, & tanta distanza Ú dal laco doue il piede si parte per unirsi con laltro a laltro piede, quanto dal loco doue si parte la mano a quel loco oue ella i ferma ˛ poco meno . stando dunque tutte le predette auertenze si deue por grandi▀ima cura nel muouer il passo a tempo con la mano , & sopra tutto non far salti, ma hauer sempre un piede fermo & stabile, & mouerlo con grandi▀ima ragione douendosi massimamente conuenir in moto con la mano la qual non deue punto uariar per niuno accidente dal suo proposito di ferir ˛ riparare.

The right leg ought always to be the strength of the right hand, and likewise the left leg of the left hand: So that if at any time it shall happen a thrust to be forcibly delivered, reason would that it be accompanied with the leg: for otherwise, by means of the force and weight, which is without the perpendicular or hanging line of the body, having no prop to sustain it, a man is in danger of falling. And it is to be understood, that the pace does naturally so much increase or diminish his motion, as the hand. Therefore we see when the right foot is behind, the hand is there also: for what who so strains himself to stand otherwise, as he offers violence unto nature, so he can never endure it: wherefore when he stands at his ward, bearing his hand wide, there also the foot helps by his strength, being placed towards that part: and when the hand is borne low, and the right foot before, if then he would lift his hand aloft, it is necessary that he draw back his foot: And there is so much distance from the place where the foot does part, to join itself to the other foot, as there is from the place whence the hand parts, to that place where it remains steadfast, little more or less: wherefore presupposing the said rules to be true, he must have great care to make his pace, h move his hand at one time together: And above all, not to skip or leap, but keep one foot always firm and steadfast: and when he would move it, to do it upon some great occasion, considering the foot ought chiefly to agree in motion with the hand, which hand, ought not in any case what soever happen to vary from his purpose, either in striking or defending.

Next - On Wards and Single Rapier